Why isn't biochar big: Part II

Last week I asked the question, Why isn’t biochar big? I hypothesized about how biochar’s foundational story divides the field into promoters and detractors, believers and non-believers. This week I’m going to focus on that sprout- and compost-heady period...the 1970s, and how one of the underlying ethoses of that era affected the way biochar grew, or didn’t.

Part 2: No, no, do it yourself

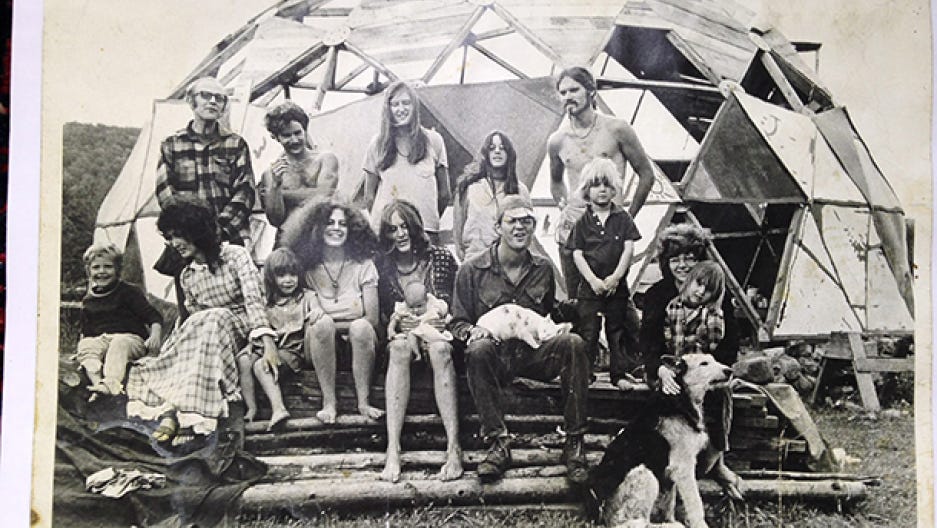

To get into the mindset of the people I’m going to be talking about--the back-to-the-landers of the 1970s--I have to set the stage. The back-to-the-land movement was a response to a bunch of historical forces, but the one that most interests me is the industrialization of agriculture, in the US and much of the developed world. Famously, chemical factories went from making nitrogen for bombs to making fertilizer. Earl Butz was Secretary of Agriculture. His message was “Get Big or Get Out.” Support for small-scale family farms were wiped from the federal agricultural orthodoxy, and over the next generation, traditional farming technologies were replaced with mechanization, chemically derived inputs, and mono-cropping.

Back-to-the-landers literally rejected agricultural industrialization, moving to their own plots of land and aiming for self sufficiency. Activists and environmentalists at heart, they were reading Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Masanobu Fukuoka’s One Straw Revolution, Bill Mollison’s Permaculture One, and aimed to rebuild a more sustainable, smaller-scale agriculture. Their outlook was predicated on the idea that the way to change the world was to change one's own way of life--to Do It Yourself, plant a tree, fight the man, make a model that works on your farm and then show the world. It is from within this philosophical context that biochar reemerged. Biochar is something you do, not something you buy.

Some leaders of the back-to-the-land movement, reaching the latter half of their careers, and early to recognize the threat of climate change, went looking for solutions and, inspired by the study of terra preta in the Amazon in the 90’s, (following Wim Sombroek’s earlier work) took up the mantle of biochar. Some examples: James Lovelock, author of the Gaia Paradigm, Stewart Brand, founder of The Whole Earth Catalog, and activist and author Albert Bates.

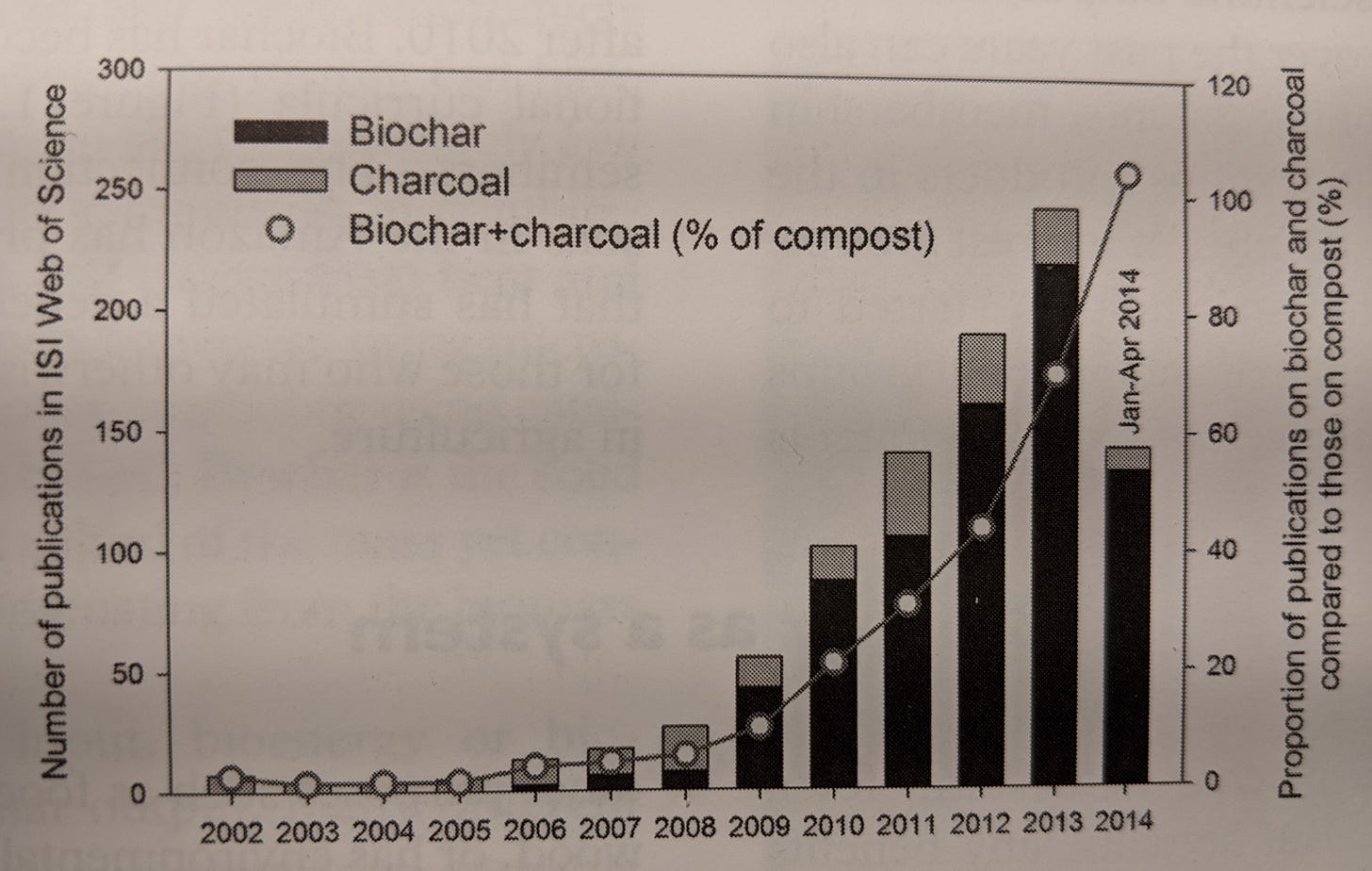

Following the study of terra preta, academic interest in the field picked back up in the 2000’s (led by Johannes Lehmann and Stephen Joseph), but this philosophical foundation created a paradox. The paradox was that the support of biochar by counterculture thinkers worked to prevent, rather than foster, the rise of a sophisticated, profitable biochar industry.

I’ll explain what I mean. The admirable and optimistic community I described above did not devote itself to making biochar companies but to making biochar. They did not encourage people to buy biochar from them, but to be like them and make biochar themselves.

Even today, I see leaders in the field encouraging people to make their own biochar--in backyards, pits, steel drums, trading designs for kilns. I get it; it’s a beautiful idea. It’s fun to make your own biochar too (I have happily experimented). But for the biochar community, and specifically for the entrepreneurs in the community, the eternal coupling of the DIY ethos to the field makes it hard to get started. Look up “biochar” and you’re almost immediately deposited into the world of how to make it yourself. When most available literature is on the minutiae of how to --1) find and gather feedstock, 2) buy, build, or dig a place to make biochar, 3) tend to the process appropriately, 4) co-compost or otherwise combine biochar with microbial life and fertilizers, and 5) apply and potential measure results--you end up with our current community-- a small field of enthusiasts.

This is the point I want to land on. If the biochar field is consistently suggesting that the real way to do it is to make it yourself, how do potential customers respond to a consumer product? I think not very well. So, despite noble intentions, the back-to–the–landers, permaculturists, and foresters who encouraged everyone to make biochar themselves unintentionally compromised the growth of a promising industry. You see this trend made manifest in biochar’s entrepreneurial community: lots of companies that sell equipment, not many successfully selling biochar.

To clarify: I am NOT against backyard production. I haven’t forgotten Wendell Berry—“How will you practice virtue without skill.” I find his message appealing and enduringly relevant. Nonetheless, when evaluating the current biochar ecosystem, one should note that by always saying “you can do it yourself!” we are creating an environment welcoming to enthusiasts and hostile to entrepreneurs. The DIY ethos embedded in the biochar community has generated a hurdle for entrepreneurs -- every potential customer that would have bought biochar was convinced they should make it themselves.

Check back next week for Part III (updated with link on 1/29).

In the meantime, check out this recent interview with Simon Manley on carbon markets, the potential for approval of a biochar protocol by Verra this year, and the profound impact that would have on the biochar community.