It’s easy to make biochar!...Or is it?

Why biochar isn't big: Part III

Last week we looked at how a DIY ethos was embedded in the promotion of biochar, and how that made it hard for entrepreneurs to build retail businesses in the sector.* This week, we tackle a thorny issue: why we should get over our romantic notions and build...lots of industrial pyrolyzers.

Part 3: It’s easy to make biochar!…Or is it?

We’ve gotten attached, for reasons I tried to parse here, to the idea that everyone should make biochar, and by an unexplained transitive property that, therefore, biochar must be easy to make.

But the more I learn about biochar, the less and less convinced I am that this is true. I now think that biochar has more in common with a hot dog than a chocolate chip cookie. (Please hear me out.) For hot dogs, industrial processing isn’t necessary. It is preferable. You can make hot dogs at home, but you probably shouldn’t. If we’re honest (and the market bears this out) hot dog making is a thing well suited to some degree of industrialization or obsessive (and well capitalized) amateurs.

The same is true of biochar.

Why? All the research I’ve done makes it clear that making biochar at home is comparatively worse for the customer and the climate. Let me break it down - how should we think about biochar production when it comes to:

The planet?

Heat utilization is key to making the carbon math work. If you’re making biochar at home, you’re not likely to be using the heat for something useful. If we’re not capturing the heat from pyrolysis, the net amount of CO2 we’re pulling down from the atmosphere drops dramatically.

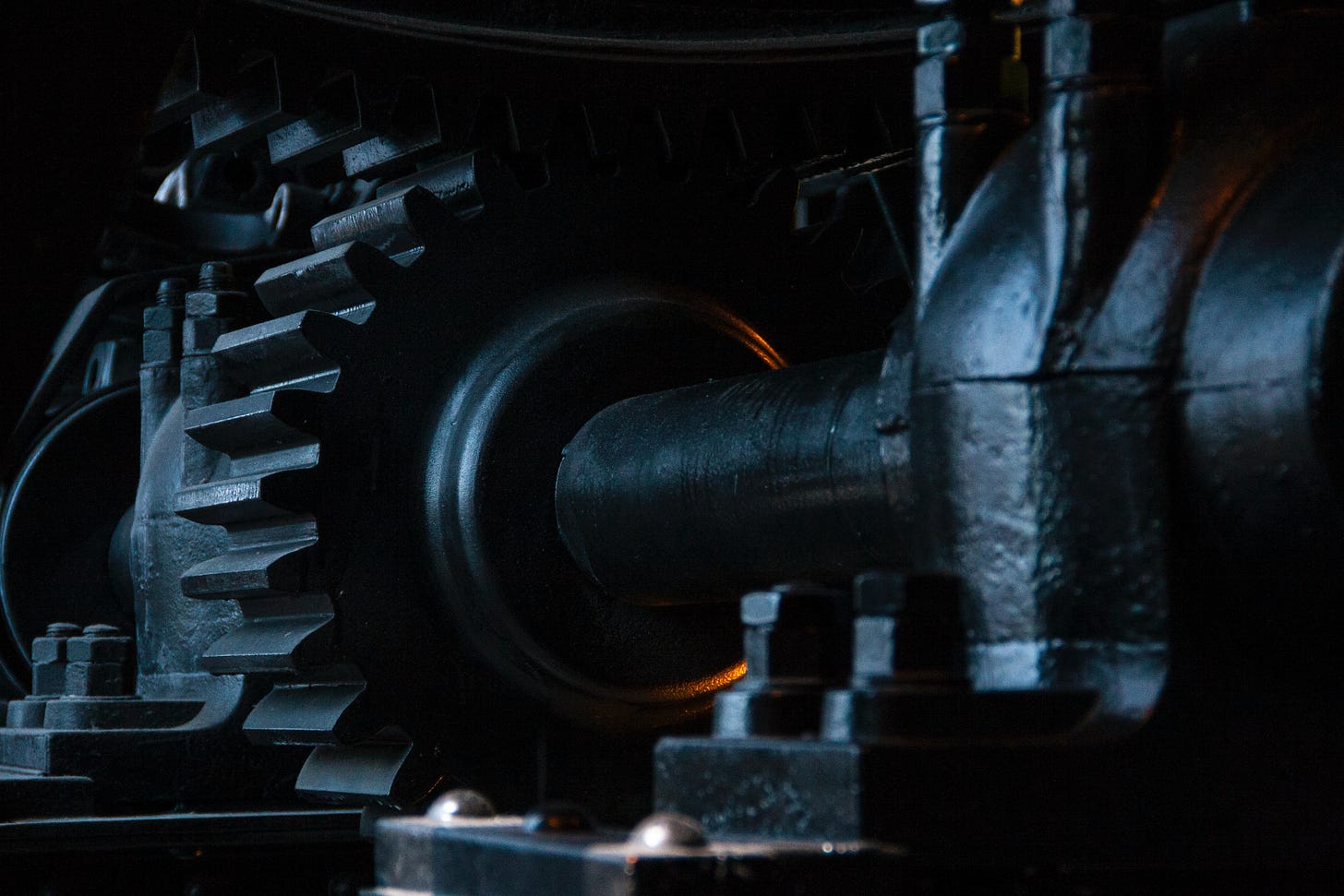

Emissions are inversely related to pyrolyzer sophistication (on a per kilo of feedstock basis). The less sophisticated the pyrolyzer, the more particulate matter is released into the air. If we think we need to make more biochar, and we’re keeping air quality in mind, better equipment matters.

There is going to be a lot of variance here, but LCA estimates for an open pit burn look something like 1.4 t/CO2e captured per ton of biochar. Systems that use the heat? About double (2.8 t/CO2e and higher) on account of the avoided emissions. That’s a big difference. Much more detail here, with the caveat that small scale pyrolyzer/cookstoves are pretty great.

The customer?

Consistent production can be difficult. Trying to balance input variables (different kinds of feedstocks, different moisture content, temperature and residence time) and output variables (ash content, carbon content, toxins like PAH and VOCs) requires a lot of knowledge and experience. The companies making advanced carbon are picking specific feedstock for specific reasons.

Processing biochar into a saleable product can get complicated. Christer from Circle Carbon set out to sell raw biochar. He found that customers weren’t getting great results when they used it as a soil amendment and they were blaming the biochar. It turns out that getting the microbial and nutrient side of biochar right isn’t an obvious step. So, Christer switched his focus to selling soil and managing the process of combining biochar and compost himself.

Matching biochar to soil needs changes yield outcomes significantly. Make the wrong kind of biochar for your soil, or apply too much or too little, and you won’t get a yield increase of 30%, as you thought. There’s a chance You might get 100%. But 5%, or -5% are also on the table. For farmers without a margin of error (and their lenders), the risk is too high.

Ref: Look at these people in the 1800’s trying to sort it out, It’s amazing how much we knew then, and how little has changed. And, a yield overview for the curious. More here on combining biochar with N.

The producer?

Making biochar yourself is time intensive. People who make biochar at home value their time. This is not a bad thing! But it increases the implied cost and thus limits the extent to which they can sell it. It’s simply too expensive to sell (like home made hot dogs, fwiw).

Carbon offsets are only feasible at scale. The complexities of getting compensated for biochar on a voluntary carbon offset platform put offset compensation beyond the reach of most small producers. Considering the value (say $60/t) and volume (most batch kilns are a few hundred pounds max per run), the cost of getting set up isn’t worth it unless you’re producing at scale.

To give an idea, I usually see bulk biochar made in batch kilns at $300-1500 a ton, but would estimate that some of the larger scale, more sophisticated operations are currently operating at more like $25-75 a ton.

One last thing: a virtuous cycle

Now, in addition to better for customers and the climate, I’m going to make one more claim. Focusing on industrial production would be better for the field. Why? Because industrial production will set a virtuous, field-building wheel a-spin: More sophisticated production will allow for more rigorous biochar characterizations. With more rigorous definitions it will be easier for entrepreneurs to build product-market fit, especially in the high value parts of the market--like phosphorus filtration--that require specific characteristics. Better product-market fit reduces the risk and increases the upside of application, increasing the likelihood and lowering the cost of project finance. Efficient project finance means larger scale and lower cost. That is how we reach scale.

So, it’s time to change our minds about this: We would be better to favor larger scale, more rigorous pyrolysis processes and better classification.** When thinking biochar, think hot dog.

Check back next week for Part IV! And, if you missed the last few parts, here is Part I, and Part II.

* I got a couple notes saying, “Yes, but there are retail biochar companies!” Absolutely true. There are exceptions to all the very broad strokes I’m painting. The question I’m really trying to answer is: why aren’t they really big (already)!

** Or smaller systems that are sophisticated, scalable, and distributed. (e.g. Takachar)

Thanks for your very interesting article. I agree that industrial production of biochar would give many benefits. In particular, as you write, it would drive product characterisation and achieve lower production costs. Also benefit from larger capital resources to invest in R&D and specialised high tech equipments, leading to higher biochar quality and achieve greater carbon mitigation.

However, I wonder if promoting and focusing primarily on industrial production capabilities could result in the emergence of a few large corporations having subsequent control over the sector ? Which in turn could harm the development of smaller businesses and entrepreneurs, as they might disproportionately attract investments and have the ability to weight on how future regulations are written.

Moreover, the technological advances made by industrial scale businesses might not benefit to the broader biochar community if they do not disclose their findings.

It is also fair to ask in my opinion, if the the drive for profit of large companies outweigh the original hopes for biochar which is to address the climate crisis and support a sustainable agriculture (amongst many other...)?

Oppositely, if those worries about large scale industries turn out to be true, how could the biochar sector be kicked off ? By funding and promoting local, small entrepreneurs and startups with public and private funding ? Where DIY like projects showed their limits as you demonstrated in your Part 2, there might be a middle ground between back garden experiments and large scale industries.

(note: I have recently discovered biochar, and I have only started to learn about it in the last few weeks. This is an attempt for me to understand the bigger picture you are brilliantly depicting here in accessible terms. Not an attempt to bluntly criticise the ideas in your post. I'd be happy to have further discussions with you.)

Well, enter the charbecue! A simple little unit that burns all kinds of odd organic material - twigs, pine cones, dried weeds, paper etc. You use it to heat you food and you take the remaining char and put it into your soil. Rough and easy but saves a lot on the cost of barbecue charcoal. You get the heat and the soil amendment. Otherwise I agree 100% with what you say. Hotdog!